I know it's anachronistic of me, but I can't help it: I read magazines, lots of them, and I read them regularly, attentively, and thoroughly. I did this even before I became so happily involved in the monthly goings-on at Open Letters Monthly (a gigantic new issue of which has just been published, for those of you who might want to spend some thorough attention yourselves), and in the last few years I've had all the more reason to respect the wit, reach, and sheer amount of work involved in pulling off a monthly publication of any quality at all (and for all I know, even the ones with NO quality are still Hell on wheels to bring to term - it's still a gigantic amount of verbiage needing to be massaged and finessed, after all).

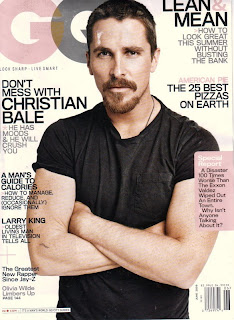

I know it's anachronistic of me, but I can't help it: I read magazines, lots of them, and I read them regularly, attentively, and thoroughly. I did this even before I became so happily involved in the monthly goings-on at Open Letters Monthly (a gigantic new issue of which has just been published, for those of you who might want to spend some thorough attention yourselves), and in the last few years I've had all the more reason to respect the wit, reach, and sheer amount of work involved in pulling off a monthly publication of any quality at all (and for all I know, even the ones with NO quality are still Hell on wheels to bring to term - it's still a gigantic amount of verbiage needing to be massaged and finessed, after all).Take the May issue of GQ, for instance. I know there are those among you (you know who you are) who deride the very idea of reading a magazine like GQ, but nevertheless: every issue comes bearing several items of interest or genuine worth. This issue features a cover story about world-class infantile moron Christian Bale (whose infamous tirade on the set of Terminator should have terminated all public interest in him of any kind), and despite such an unpromising opening, I read the whole thing scrupulously, cover to cover - and once again, I wasn't disappointed.

Some of the items in the issue were admittedly trivial (jebus gawd, the amount of space they waste talking about idiotic stuff - utterly fad-driven things and gadgets I guess the magazine's target demographic really is wealthy and stupid enough to amass and care about amassing), like the squirt of irritation I felt seeing that stupid Gillette ad that shows the same ass-faced young douchebag in like fifty different iterations of douchery - or the fond smile I cracked at another ad, featuring the very same all-grown-up tobacco addict Alex Pettyfer who is, as all the world knows, the idee fixe of my esteemed (and hilarious) fellow-blogger Vera, and I laughed out loud at transcribed chatter between GQ's "in-house Twilight enthusiast and Pattinson-picture-kisser" Raha Naddaf and a random bunch of Twilight fans contacted at a sleepover:

What do you think about the rumors that Pattinson dated Camille Belle?

[Thirteen seconds of mortified screaming]

Olivia: We don't like her.

[Three-minute conversation about the Jonas Brothers, with one girl concluding, "They wear promise rings, but that doesn't mean anything."]

Now for the big question: Do you ever imagine yourself making out with Pattinson?

[Again with the silence]

Abigail: We're only 12.

Hee.

There was also a throwaway photospread of a brand-new pro quarterback named Alex Sanchez, who was convinced to pose in a series of Baywatch-dorky beach outfits, presumably in exchange for permission to manhandle the vacant-eyed young thing posing in the photos with him. He doesn't seem able to fully shut his mouth, so he probably has a bright NFL career ahead of him.

There was also a throwaway photospread of a brand-new pro quarterback named Alex Sanchez, who was convinced to pose in a series of Baywatch-dorky beach outfits, presumably in exchange for permission to manhandle the vacant-eyed young thing posing in the photos with him. He doesn't seem able to fully shut his mouth, so he probably has a bright NFL career ahead of him.But the issue wasn't all fun and games. Peter Savodnik turns in a riveting freelance piece on the Russian "Maniac" serial killer Alexander Pichushkin, who lured dozens of men and women into the woods of Moscow's Bitsevsky Park (three times the size of Central Park), killed them, and then dumped their bodies down municipal wells, where the sewage system washed the remains varying distances from the scene of the crimes (in typical serial killer fashion, Pichushkin got sloppier and sloppier the longer he went unsuspected and uncaught - which guaranteed he'd eventually be suspected and caught). Savodnik's article is very good - if grisly - reading, except for one odd bit of reaching he does that had me scratching my head:

... the detective who led the investigation ... rules out the possibility that the Maniac is homosexual. He says Pichushkin doesn't have any sexual longings for men; he just doesn't care about women.

But there's something else: In Russia, which remains violently homophobic, it may be that people have a hard time believing a gay man is capable of the kind of power or force of will that defined the Maniac. The Maniac is a maniac, and he's evil, and no one disputes this, but he is also very much a man in the way Russians think of men.

Hard to know what Savodnik is getting at here - so Pichushkin might be gay because his investigators might be typically bigoted Russians? He displays the absolutely textbook serial killer lack of any sexual identification, and suddenly that's enough to cast a doubt? Granted, I'm not the expert on the Maniac that Savodnik undoubtedly is by this point, but this still seems like a weird bit of projecting to me. Sometimes, a maniac is just a maniac, after all.

And only a couple of pages from the retailing of Pichushkin's homicidal horrors is a story about a real murderer, a serial killer of a scope and professionalism that makes the Maniac look like a piker: former defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld is profiled by the very talented Robert Draper, with predictably chilling results.

As I read the piece, as I encountered quote after quote like this one:

"What Rumsfeld was most effective at doing was not so much undermining a decision that had yet to be made as finding every way possible to delay the implementation of a decision that had been made and that he didn't like"

I gradually realized that I know Donald Rumsfeld - I used to work with him. I had a co-worker who was every bit as mulishly self-absorbed and vigorously un-helpful as Rumsfeld is everywhere portrayed here as being. That co-worker could absolutely 100 % be relied upon to make any - and I mean any - work-related thing, no matter how big or small, no matter how important or trivial - more difficult, more annoying, more of an issue. You'd be off doing something else, and you'd suddenly realize the phone had been ringing for fifteen minutes - and when you hurried over, absolutely frickin guaranteed this co-worker would simply be standing there, obdurately ignoring the phone - and if you were dumb enough to ask why, he'd have a long, breathlessly self-centered rationale for why he'd been ignoring the phone, and it wouldn't matter what the Hell it was, because by the point of you being dumb enough to ask for it, you'd be stuck in it, trapped in the cramped, sweaty little mental world of somebody who's just one compass-tick north of being genuinely, helplessly, institutionalizably insane. Like that co-worker, the Rumsfeld in Draper's article gains absolutely nothing by his reflexive, non-stop obstructionism - and like that co-worker, the only reason his knee-jerk adamantly petty assholery didn't get him fired instantly is because nobody sane wants to interact with him long enough to get that firing done, because interacting with such a useless piece of cowdung, such a pathetically arrested 5-year-old, is intensely soiling. Reading this article, it was no shock to me that President Bush fired Rumsfeld on live TV, far away from the man himself. No shock either that at the man's farewell dinner, he intensely creeped out his guests - he probably ate every last morsel of the free food, too.

But as disagreeable as that article's subject might be, the article itself was a thrill to read - and it wasn't alone in this issue, and every issue of GQ is like that. So I keep reading, even though I don't know a Blackberry from a blueberry and couldn't tell you what kind of wood is best for your $500 loafer-tree.