Since about 250 pages of the latest

Atlantic Monthly are devoted to Joshua Green's profile of Hillary Clinton, it seems only right to start off with that - and to note right away that Green comes off as ... well, not to say 'an asshole' but certainly a CAD.

He spends the gigantic bulk of the article maintaining all the bells and whistles of journalistic objectivity - the hours logged with his subject, the tells-it-like-he-sees it descriptions, the wide-ranging secondary sources. For 249 of its pages, I was reading intently and learning something on every page.

Then I got to the last paragraph and uttered a 'what the fuck?' that I'm sure was also uttered in a certain breakfast-nook in Chappaqua:

Yet it is fair to wonder if Clinton learned the lesson of the health care disaster too well, whether she has so embraced caution and compromise that she can no longer judge what merits taking political risks. It is hard to square the brashly confident leader of health-care reform - willing to act on her deepest beliefs, intent on changing the political climate and not merely exploiting it - with the senator who recently went along with the vote to make flag-burning a crime. Today Clinton offers no big ideas, no evidence of bravery in the service of a larger ideal. Instead, her Senate record is an assemblage of many, many small gains. Her real accomplishment in the Senate has been to rehabilitate the image and political career of Hillary Rodham Clinton. Impressive though that has been in its particulars, it makes for a rather thin claim on the presidency. Senator Clinton has plenty to talk about, but she doesn't have much to say.Yeesh. I'm guessing somebody's access-codes have been shredded ...

The issue also features a heartfelt though somewhat scatter-brained tribute to YouTube written by Michael Hirschorn. Like so many writers who set out to describe just exactly what YouTube is revolutionizing and just exactly how it's doing so, Hirschorn quickly loses his way and begins nattering (amazing how lenient we become toward this - nattering, but extremely well-paid nattering in a premium forum ... the latter two qualities, you'd think, disqualifying the former; personally, off the top of my head, I can think of four people I know who could have written this piece better, ALL of whom would benefit immensely - personally and professionally - from having a piece published in the

Atlantic).

Of course I, like everyone else, worship YouTube. I spend at least 30 minutes a day there, indulging in every stray whim of visual curiosity. College girls puking in plain view? You got it! Precision-flying plane slamming into a crowd of spectators? You got it! Surging ocean waves at sunset? You got it! Insane basset hound named Lucy having a fit right in front of the camera? You got it!

I'm not convinced that it spells the death-knell of anything, let along movies and tv, but nevertheless: I'm entranced. If I could figure out how to TRANSPLANT YouTube videos onto these posts (as even a casual glance at other blogs reveals EVERYBODY else knows how to do), I'd be treating you all to my latest finds practically every day. But alas, the last time I called up one of my young friends and asked him to give me step-by-step instructions on how to import something to my site, my phone's battery died (and the sun came up) while he was still going strong.

So in the meantime, you'll have to make do with typing 'crazy cat' and 'crazy dog' into YouTube yourselves! Endless hours of mindless fun!

Of course, there are those who would say that if you're willing to plug yourself into YouTube, you're one step closer to being willing to LIVE video games all the time. Lots of those people are quoted in Jonathan Rauch's article on video games in this issue.

Much space is devoted to how COMPLEX video gaming technology is becoming, how the graphics and sound effects are becoming more and more lifelike all the time, how the interface of user-interaction is getting more and more complex all the time.

The piece concludes with this:

We can't know where the quest to build interactive drama will lead, but we do know that the dramatist's tools are the oldest and most potent of all emotional technologies. Sooner or later, drama will converge with the video game, the newest and most vibrant of all entertainment technologies. And then? Not long ago, I attended a stage performance of Aeschylus' The Persians,' the most ancient work of the dramatic literature. Even in translation and at a remove of 2,500 years, it left an audience of modern Americans feeling stunned and disembodied, as if the intervening millennia had disappeared. Wow, I heard myself think, if I could play that, I'd be so excited!To put it mildly, there's a lot wrong with this. We'll pass over that bit about stage-plays being referred to as 'entertainment technologies' and focus on the central nub of the issue, the one I focus on with all the hundreds of video game addicts I know.

You know them too, I guarantee it. You're statistically likely to BE one yourself. These are the young people who, when you ask them at work or school every morning what they did the evening before, sheepishly offer vague non-answers: 'nothing,' 'not much,' 'stuff' .... because the real answer, in each and every case, is: "I played video games from 6:30 pm until I passed out, between 2 and 4 am, fully clothed but unfed and unwashed."

Some of these people might say this sordid little truth out loud once - it'd be good for an office chuckle. But none of them would ever say it as many times as it actually happens, because it happens every single time they have free time of any kind. 10 page papers with footnotes are written on the B line on the way to the class where they're due, so that radioactive mushrooms can be detonated from 6:30 pm to 4:30 am.

Some of these addicts are intelligent young people, and some of them have in the past attempted to defend or even justify their addiction to me, on just the same grounds as the above ridiculous quote does: that video games AREN'T just passive thumb-exercises. That they have depth and worth and dramatic power and even (in one arguer's disasterous case) LITERARY merit.

I realize nobody wants to admit when they've let something into their lives they can't control, but this is just silly. Rauch here is being willfully blind to the gaping problems in his own assertions.

The reason his modern American audience was enraptured by 'The Persians' has nothing to do with 'entertainment technology' - it arose from the fact that Aeschylus, the play's single, human author, used a combination of intellect, historical knowledge, intuition, and most of all poetic talent to craft a thing that would draw an audience in and work a deep impression on them.

But he didn't specify WHICH impression, or which shades of different reactions each person would feel. I'm sure no two of Rauch's fellow audience-members felt the EXACT SAME exhilaration over the performance - it would be altered by their seat-mates, their view of the stage, their knowledge of Athenian history, their experience of life and of theater. In other words, although everybody in the audience would be moved by the power of 'The Persians,' no two audience members would have seen the exact same play.

That's literature's central power: its ability to transform us, individually.

Nobody has ever been transformed by a video game (well, except for those few - their number grows every year - who, by playing literally non-stop, managed to transform themselves from living to dead), and nobody ever will be. And the reason is simple: video game users are entirely passive. All their possible interactions with their game are pre-programmed, and knowing this prevents them from CARING what their own reactions are to anything that happens.

While stage plays seem on the surface even less flexible (Hamlet never lives; Mary Tyrone never takes up jogging), Rauch could testify that in reality they're far moreso - since when they're done well they form an intensely interactive, intensely individual bond with each member of the audience, and audience that, through the strength of that bond, VERY MUCH cares about its own reactions.

All of which is already known to video game addicts - they weren't advancing their argument in any kind of sincerity. They were just killing time until they can get back to their hand-controls.

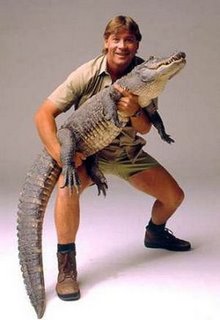

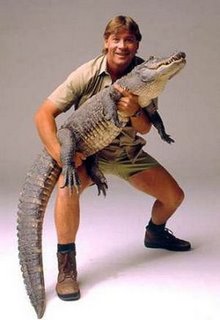

Still, as irritating as I found this video game piece, I'm afraid top irritation honors for this issue go to the regular 'Post Mortem' feature, this time eulogizing 'crocodile hunter' Steve Irwin.

We here at Stevereads have little patience with the old nostrum about not speaking ill of the dead. We think it probably originated in the Middle Ages, when there was a good chance the dead would pop back out of the ground and SMACK your ill-talking pie-hole. But nowadays, thank to 'C.S.I.' our dead STAY dead, so we're free to ill-talk our heads off.

And what's the point of it anyway? It does a disservice to the truth to whitewash ANYTHING. If I were ever going to be dead, I'd like to think my friends would be frank about my shortcomings (and if me being dead was offered hypothetically, my having shortcomings is SO much moreso...), just like I'd want my enemies to at least grudgingly admit my good points.

That being said, some of you may already know what I think of this opportunistic blockhead Irwin.

But if you didn't know, this post mortem, written in high priggish style by Mark Steyn, would take you on a guided tour of all my reasons.

Steyn takes the same line on Irwin that Irwin took on himself during his brief, unbearable tenure as something that could be passed off for a kind of sort of 'naturalist.'

Irwin died of a stingray barb to his heart, as most of you know. Any guesses on how you get a stingray to barb you in the heart? Let me tell you, since my freakish little nature-boy Elmo never speaks on this blog: you pick one up and FUCK with it. Otherwise, you - and it - are perfectly safe.

Steyn quotes Irwin on the subject:

We can't keep looking at wildlife on a long lens of a tripod. Then there's this voice of God telling you about the cheetah kill. After 450,000 cheetah kills, it's not entertaining anymore.That's Irwin in a nutshell: the pseudo-naturalist for the video game age. An adult cheetah accelerates to 70 mph in under seven seconds; its frontal cortex analyzes course-changes in its intended prey so fast that neuroscientists can't tell you how the brain tissue in question can do it; the entire hunt takes roughly fifteen seconds from start to finish, and the smallest mishap can result in a broken leg for the cheetah, thus death. In the entire animal kingdom, just about three creatures rely on the adaptation of spectacular speed-bursts to secure their prey.

But is that 'entertaining' enough for the joystick generation? NOOOOOOO.

It makes matters worse, very much worse that Steyn decides to burnish Irwin by tarnishing somebody who does it right: believe it or not, David Attenborough comes in for a paragraph of trashing:

In the presence of animals, he lowers his voice to a breathy whisper ... Sir David keeps his breathy whisper even when he's back in the BBC studio doing the voice-over.Well, OK, except: no he doesn't. He keeps the 'breathy whisper' (note the sneer associated with feeling awe or reverence for the natural world ... pshah! what's this simp THINKING?) only when he's doing voice-overs for on-site lines uttered in that whisper that didn't come out clearly on tape - his actual in-studio voice-overs are all done in normal voice.

The differences, of course, go much deeper. Attenborough has studied birds and animals his entire life; all that Irwin knew about the animals he FUCKED with was what he hurriedly glimpsed on his cue cards.

I watched a program of his once - he was in India, and some local residents told him there was a 20-foot anaconda living in a nearby drainage ditch. And that was all it took: without further ado, while the cameras watched, Irwin walked over to the open brackish ditch and lept in - I remember thinking 'the man is insane, literally insane - he has no idea if the anaconda is anywhere nearby, no idea if four or five actually poisonous snakes are in the ditch, no idea what skin-fungi he'll pick up, some of them untreatable, some of them fatal. '

I remember asking myself: why on Earth would anybody DO such a stupid thing?

Subsequent viewings gave me my answer. The entire thing was about money - Irwin grabbed at ratings the way he grabbed at wildlife. It turns out he did both ineptly - TV sees no better nature-ratings than David Attenborough's, and it's a little unlikely that Sir David will ever die by a sea-snake up his ass.

A tragedy for Irwin's wife and family, yes, and I suppose his viewers will miss him for the five minutes it takes to find another lunkhead adrenalin junkie to jump into drainage ditches.

But in my limited but valid brief as spokesman for at least a corner of the animal kingdom (the wonderful branch of canidae! One can't help but notice that Irwin never decided to FUCK with any kind of wild dog; he might not have known much about wild exotica, but give the man credit: he could sense when he stood a good chance of being ripped apart like a fat rag-doll), I have to say: good riddance.

The immense marvels of the natural world - those who've survived the onslaught of humanity - aren't here for the ratings-amusement of mankind. They are their own gorgeous, incommunicable worlds, and naturalists like David Attenborough understand that. Jackass croc-jumpers like Steve Irwin not only don't but don't WANT to.

So: the 'crocodile hunter' got a stingray barb in the heart. Great final-ever ratings stunt, but please: let's have no others.