Though not worthy of inclusion with the Eagleton/Dawkins donnybrook, there were a couple of other things worth mentioning about the latest London Review of Books this time around.

For instance, there's this letter from Russell Seitz of our own Cambridge Mass.:

Back in Nasa's glory days, even photographers were kept 17,000 feet away from the Apollo 11 launch pad - about a mile per kiloton of explosive yield were the Saturn V to suffer a mishap. Yet one enterprising colleague of mine slipped away down a canal to a point two miles closer. The lift-off safely hurled the 'spam in a can' astronauts moonwards, but the wayward journalist emerged hours later, stone deaf and looking like Wile E. Coyote on a bad day. He recovered sufficiently to take the press bus to the base of the launch pad, which we were aghast to find sprinkled with Saturn V nuts, bolts, and other bits shed during lift-off. Nasa declined to comment, but a Mercury astronaut later explained their significance. Any damn fool can get close to a virtual hydrogen bomb, but it takes the right stuff to climb into one fully aware that it had been built by the lowest bidder.

Bravo, Russell! Thanks for at least trying to convey how an earlier generation looked up to its astronauts ...there's no equivalent today - or rather, I should say today's society isn't equivalent.

Also good in this issue was a review by Peter Campbell of the new exhibit at the Tate of Hans Holbein's drawings and portraits.

Campbell is a very good, very sensitive reader of Holbein's work - work which has always been deeper and more mischievous than it seems at first blush.

He begins with an extended conceit that's so irrestible I immediately wanted somebody to WRITE it, as a novella - except I'm the only person I know who could write it, and I'm kind of busy:

Imagine a party attended by sitters from English portraits. The Gainsborough crowd rustle in, a blur of silk and powder. You can't quite bring their faces into focus, but you seem to recognise them. They are elegant and casual. The people who come with Reynolds are their contemporaries, but the atmosphere changes. The men have more gravitas and fall naturally into classical poses, the women are winsomely theatrical. The aristocratic Van Dycks tend towards the soulful and control the arrangement of their pedigree-revealing features, their gestures and their ringlets with an exquisite care that intimates carelessness. The Lelys tumble through the door from another party - the men's coats unbuttoned, the women's bosoms as white as their eyes are bright. The Hogarths, a decent, prosperous lot, are here for the food and drink. The Hilliards - some in allusive fancy dress - are full of poetry. The Freuds, who haven't dressed up at all, slump in armchairs. Some of them fall asleep.

"Imagine such a party and you see that while individuals differ - and while successful portrait painters must, in getting a likeness, preserve differences - painters also turn their sitters into types, sometimes, but not always, flattering ones...

"What distinguishes the Holbein contingent at the party is that they don't know there is a party. Holbein doesn't suggest congeniality by imposing his personality on their personalities. You will remember each face, and would recognise it years later in an identity parade, but as itself, not as one managed by Holbein.

Although none of you care about Holbein portraits any more than you care about Chilean water-additives, I liked this bit. Holbein - volatile, explosive, every inch the 'tempermental artist' - would have loved this description.

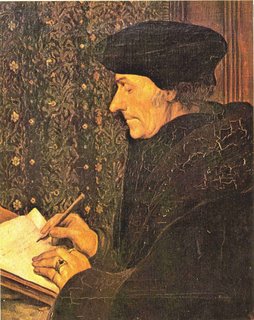

Holbein's portrait of Erasmus is a little marvel, we here at Stevereads can attest directly. The great man, the middle-aged world-famous humanist, is sitting bolt upright at his cantilevered writing table. He's dressed thickly, against the perennial cold of all 16th century houses, but there's another reason too: the robes and cap he wears are costly things, signs of the commercial bankability of the sitter.

His spatulate hands are at work on some enterprise of the mind or soul, but on his fingers are rings of jewel and gold, remunerable artifacts.

He's almost smiling, this man who never in life stopped smiling. He's wearing heavy clothes against the chills that always plagued him. He's not working, but you can tell from the semi-ironic cast of his long, expressive face that he KNOWS he's not working, that he knows he's pretending to work for the sake of the painting. 'Look,' the painting says, 'This is Erasmus; this is what he does, and he's obviously successful doing it.'

Easily the most impressive thing about the painting is exactly what Campbell says: once you've seen it, you know above all just what Erasmus actually LOOKED like. It's a rare thing to combine that ability with genuine artistic sensibility, so if one of you loyal readers would like to pony up the funds to send me to the Tate, I promise to blog all about when I get back!

2 comments:

Great post, Steve... Its' been quite a while since I thought twice about Hans Holbein - thanks for reminding me! I do love the portrait of Erasmus.

The neat thing to notice about the two portraits you point out are the little, telling details: for instance, in the More portrait, he's quite accurately pointed out as SWEATING - because the portrait was commissioned over a fairly hot week during which More was forced (by Holbein's professional pickiness) to wear his costly robes of state for each sitting. Likewise, Cromwell is squinting not because he was aware of the evils he'd himself soon be committing but because he was the ultimate suck-up, and Henry himself had set the pattern of great men squinting in their portraits - not to show deviousness, but to show a Tudor kind of determination (luckily, styles of physiognomy had changed by the time his homely daughter came to power)...

Post a Comment